ʿAzīz or ʿUzayr? Re-examining Qur’an 9:30 Beyond Dogma

Qur’an 9:30 is one of the most debated verses in Islamic scripture:

“The Jews say, ‘ʿUzayr is the son of God,’ and the Christians say, ‘The Messiah is the son of God.’ That is their statement from their mouths; they imitate the saying of those who disbelieved before. May God destroy them; how they are deluded.”

The Problem

Jewish history contains no evidence that Ezra (ʿUzayr) was ever called the “son of God.” This has long puzzled both Muslim and non-Muslim scholars. Mainstream exegesis solves the problem with appeals to lost traditions or fringe sects — but such explanations lack evidence.

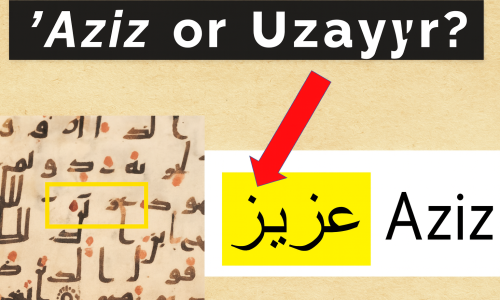

ʿAzīz as the Alternative Reading

Early Qur’anic manuscripts were written in rasm, without dots or vowels. This means that ʿUzayr (عزير) and ʿAzīz (عزيز) would appear identical. A single dot above the letter changes the reading.

ʿAzīz (from the Hebrew/Aramaic ʿOz / Aziza) is a well-known epithet in Jewish tradition. It means “mighty, precious, beloved” and is applied to the Davidic king and the Messiah in Psalms, Targums, Midrash, and even the Zohar.

Evidence from Jewish Sources

- Psalm 2:7: “You are my son; today I have begotten you” — applied to the Davidic king.

- Targum Psalm 110:2: uses Aziza (mighty/precious) as a messianic title.

- Midrash Tehillim: interprets “Son of God” language for the Messiah.

- Zohar III:276b: calls the Messiah “Aziza of God.”

This shows that Jewish tradition did apply sonship language to figures under the epithet Aziz/Aziza, but never to Ezra.

Qur’anic Symmetry

Note the structure of 9:30:

- “The Jews say ʿAzīz is the Son of God.”

- “The Christians say the Messiah is the Son of God.”

Both are titles, not names. This symmetry is broken if we read “ʿUzayr,” but restored if we read “ʿAzīz.”

The Role of Diacritics

Later Islamic tradition insists that every dot and vowel is divinely preserved. But the earliest Qur’an manuscripts had none. The difference between “ʿAzīz” and “ʿUzayr” lies in human-added diacritics, not in the original rasm.

The Qur’an itself acknowledges that ambiguity exists: Hajj 52–53

What about Muhammad?

Even “Muhammad” may not have been a personal name, but an epithet: “The Praised One,” parallel to maqām maḥmūd in Qur’an 17:79. Just as Messiah and ʿAzīz are titles, so too Muhammad may be best understood as a title, not a name. Qur’an 9:30 thus works entirely within the framework of titles and exalted epithets.

Conclusion

The traditional reading “ʿUzayr” lacks historical support. The alternative “ʿAzīz” is linguistically valid, textually possible, and historically grounded. It restores Qur’anic symmetry and makes the polemic meaningful. In light of manuscript evidence and Jewish tradition, 9:30 is best understood as addressing both Jews and Christians for exalting their leaders with titles of divine sonship — ʿAzīz and al-Masīḥ.

For Light in Darkness (lightin.co.in)