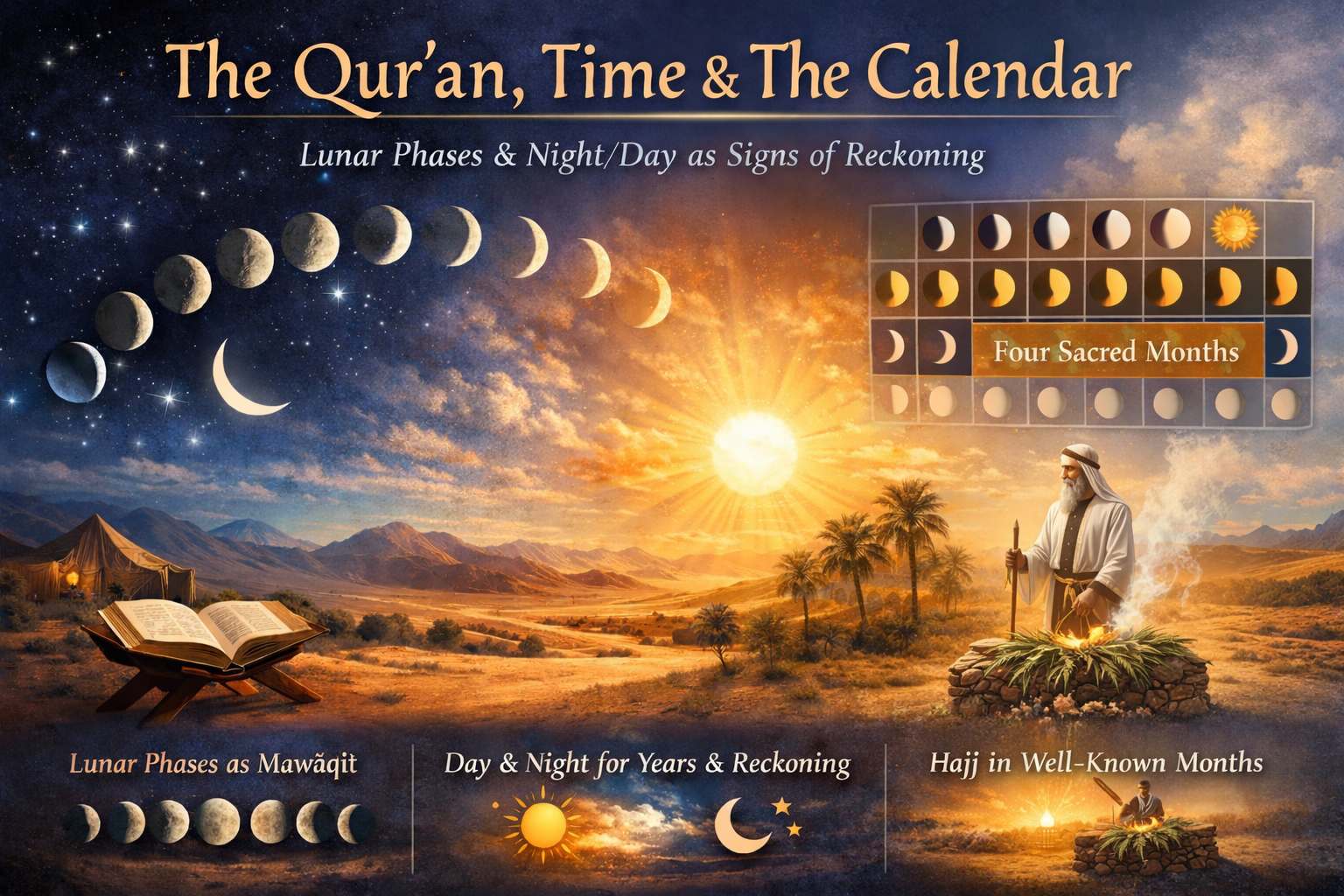

The Qur’an, and the Calendar

Why neither a purely lunar nor a purely solar reading does justice to the textThesis: The Qur’an does not “invent” a calendar. It confirms that time is built into creation and then corrects the abuse of that time-order. Key terms are the lunar phases as mawāqīt (scheduled temporal markers) and night/day as signs enabling the number of years and reckoning.

1) The Qur’an does not create time — it presupposes it

The Qur’an anchors the structure of time in creation itself:

“Indeed, the number of months with God is twelve… from the day He created the heavens and the earth…” (Q 9:36)[1]

This is not a “how-to” for drawing a calendar table. It is an ontological claim: the monthly structure of time is not a human invention. Yet the Qur’an also addresses practice, because humans can manipulate that structure (as the following verse on nasīʾ indicates).

2) “Al-Ahillah” is not a single “new moon” — it is a system of recurring markers (Q 2:189)

When asked about the moon’s changing appearances, the Qur’an answers:

“They ask you about the ahillah. Say: they are mawāqīt for people and for the pilgrimage.” (Q 2:189)[2]

Key points:

- al-ahillah is plural: it does not naturally denote a single “new moon moment,” but a recurring series (a phase-based system).

- mawāqīt (from mīqāt) denotes appointed times, scheduled terms, fixed temporal slots—a practical time-structure used for real human organization.

- Conclusion: the Qur’an here affirms a functional calendrical logic: lunar phases serve as structured temporal markers for human affairs and for Hajj.

3) Night and day as computational signs for “the number of years” and “reckoning” (Q 17:12)

The Qur’an adds a wider computational layer:

“We made the night and the day two signs… so that you may know the number of years and the reckoning.” (Q 17:12)[3]

This verse does not say “follow only the sun,” nor does it reduce time to a single cycle. It explicitly targets the result: the number of years (ʿadad al-sinīn) and reckoning (al-ḥisāb). That is the language of calculation across cycles, not mere habitual custom.

Simple logic: day/night provides the basic visible unit for work, travel, and measurement; lunar phases provide recurring monthly markers; and “number of years + reckoning” indicates a composite framework in which yearly totals are obtained by computed alignment rather than by selective citation.

4) Hajj in “well-known months” (Q 2:197): the Qur’an assumes an existing framework

Hajj is not presented as a newly invented institution. The Qur’an states:

“Hajj is [in] well-known months…” (Q 2:197)[4]

“Well-known” implies a pre-existing social memory and an already recognized temporal frame. The Qur’an intervenes where there is dispute, abuse, or corruption, rather than re-writing a full calendar manual.

5) The four sacred months: recognized, but subject to manipulation (Q 9:36–37)

The Qur’an states that among the twelve months are four sacred months (Q 9:36) and immediately targets the practical problem: tampering with time (nasīʾ) (Q 9:37). The point is not to “invent” sanctity, but to prevent humans from rearranging sacred time to suit power or advantage.

Notably, the Qur’an does not narrate “when” these months became sacred. That silence functions as presupposition: the audience already recognizes the concept, while the Qur’an corrects its distortion in practice.

6) Two opposite camps — the same methodological error

In practice, readers often force a false polarity: purely solar vs. purely lunar. Both camps frequently commit the same error: selective reading to protect inherited practice.

- Purely solar readings emphasize “years” and “day,” while sidelining Q 2:189 (lunar phases as mawāqīt), Q 9:36 (twelve months), and Q 2:197 (Hajj in months).

- Purely lunar (traditionalist) readings emphasize crescent-based month-starting, while downplaying Q 17:12 (years + reckoning), the broader idea of computed time, and the integrated logic that emerges when the Qur’an is read as a whole.

The Qur’an itself holds both dimensions together: signs of day/night, lunar markers, months, years, and reckoning. The moment a system must erase one set of verses to survive, it is the system—not the text—that is unstable.

Conclusion

The Qur’an does not publish a “calendar table,” yet it clearly affirms a calendrical system grounded in created signs:

- Lunar phases are mawāqīt—scheduled temporal markers for people and for Hajj (Q 2:189).

- Night and day are signs enabling the number of years and reckoning (Q 17:12).

- Twelve months belong to the created order, with four sacred months, alongside condemnation of manipulation (Q 9:36–37).

- Hajj is situated in “well-known months,” implying a known framework rather than a newly invented calendar manual (Q 2:197).

One sentence: The Qur’an does not invent time; it restores people to the correct use of time—without selectively silencing verses to defend tradition.

Footnotes

- Q 9:36 — “ʿiddat al-shuhūr… ithnā ʿashara… minhā arbaʿatun ḥurum.”

- Q 2:189 — “yasʾalūnaka ʿani l-ahillah… hiya mawāqīt lil-nās wa-l-ḥajj.”

- Q 17:12 — “li-taʿlamū ʿadada l-sinīn wa-l-ḥisāb.”

- Q 2:197 — “al-ḥajju ashhurun maʿlūmāt.”