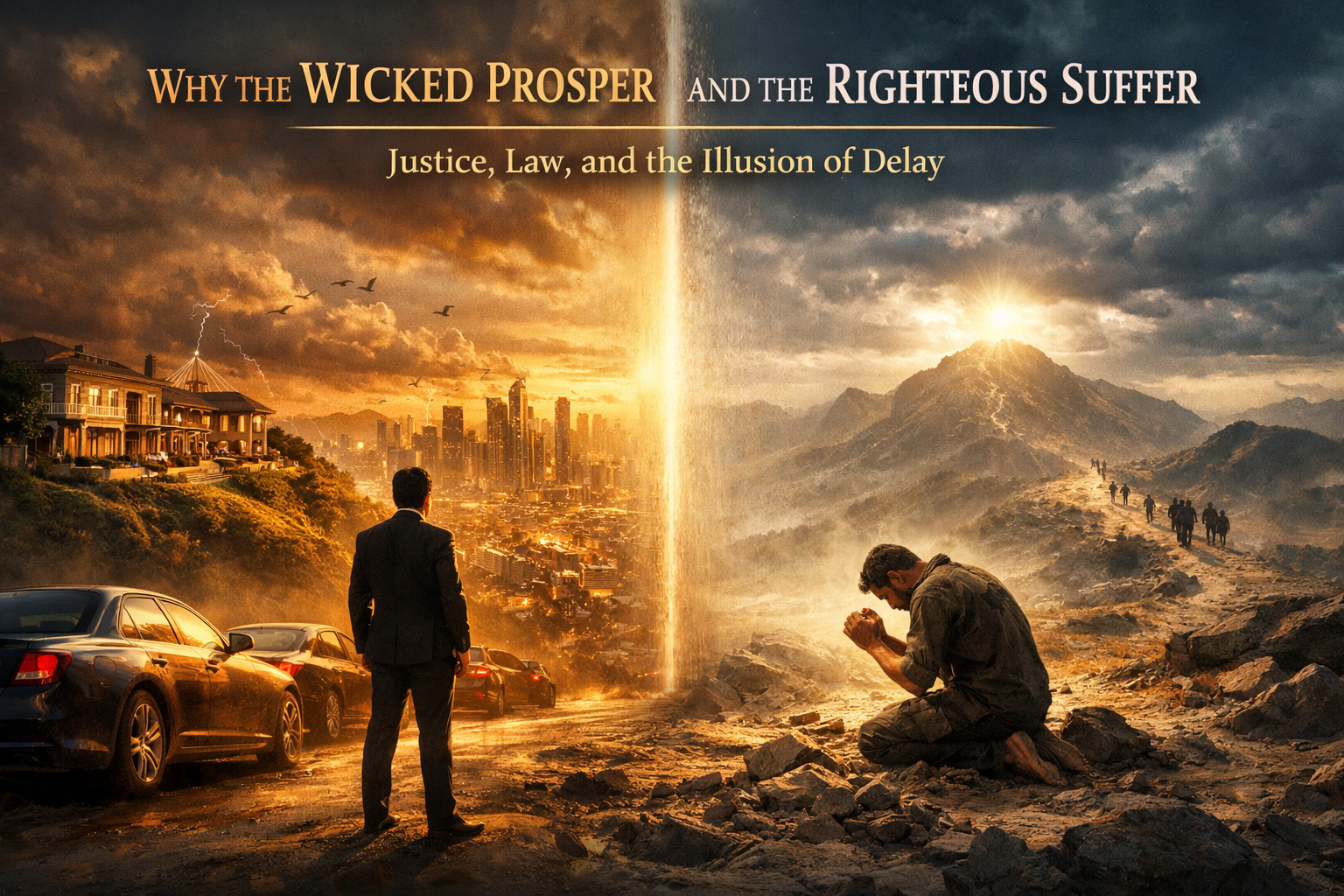

Justice, Law, and the Illusion of Delay

1. The Problem as It Is Honestly Observed

The claim that “the wicked prosper while the good suffer” is not a modern complaint nor an atheist critique. It is a foundational observation of wisdom literature itself.

The ancient texts do not deny the appearance of injustice. They challenge the interpretation of that appearance.

2. Sirach: A Warning Against Premature Judgment

The core principle is articulated with striking restraint in Sirach:

“Do not envy the success of a sinner,

for you can never be sure what his end will be.”1

Sirach does not claim that sinners fail to prosper. He asserts that prosperity is not the final metric.

The error lies not in observation, but in closing the ledger too early.

3. Psalms and Ecclesiastes: The Paradox Is Acknowledged, Not Resolved

The Hebrew wisdom tradition agrees and deepens the tension:

- Psalms observes that the wicked flourish like green trees, only to vanish suddenly2.

- Ecclesiastes states plainly that righteous men receive what the wicked deserve, and wicked men what the righteous deserve3.

Notably, Ecclesiastes offers no theological repair. The paradox is left standing, not explained away.

4. The Qur’an: Prosperity and Hardship as Tests, Not Verdicts

The Qur'an confirms the same structure:

“Do not be deceived by the ease with which the disbelievers move about in the land.

It is but a brief enjoyment…” (3:196–197)4

Prosperity here is explicitly:

- temporary

- misleading

- non-indicative of approval

“Do people think they will be left to say, ‘We believe,’ and not be tested?” (29:2)5

Comfort is not proof. Testing is the measure.

5. The Qur’an’s Rejection of Prosperity Theology

The Qur’an directly confronts the faulty logic that equates ease with divine favor:

“When his Lord tests him and honors him, he says, ‘My Lord has honored me.’

But when He restricts his provision, he says, ‘My Lord has humiliated me.’

No!” (89:15–17)6

The text identifies this reasoning as false interpretation.

Ease and hardship are both instruments of examination, not moral verdicts.

“When good fortune comes, some men say, ‘I have led a good life, and this is my reward,’ or ‘This results from my own efforts.’ If misfortune befalls them, they say, ‘This is the fault of some other,’ or, ‘This is a chastisement from above.’ I say to you, all things flow from your own destiny; good and bad are sent alike to test you; both can be turned to your own benefit or your own undoing.” 7

This Kolbrin passage mirrors precisely the Qur’anic correction in 89:15–17, identifying the same human misinterpretation of fortune and hardship, and defining both as instruments of testing rather than indicators of divine favor or rejection.

The same principle is expressed succinctly in Sirach, which likewise refuses to equate prosperity with divine approval or hardship with divine rejection.

“Good fortune and bad, life and death,

poverty and wealth — all come from the Lord.” 8

6. Effort, Consequence, and Moral Accounting

Another Qur’anic axiom aligns precisely with Sirach and Kolbrin:

“Man shall have nothing except what he strives for.” (53:39)9

There is no concept of:

- magical erasure of consequence

- prayer as transaction

- worship as leverage

Justice unfolds through process, not instant intervention.

7. Kolbrin: Suffering as Formation, Not Punishment

The Kolbrin Bible articulates explicitly what the other texts imply:

- God is not a merchant trading worship for comfort (GLN 2:15)

- Suffering is necessary for development (WSD 1:22)

- Debts cannot simply be erased without nullifying growth (GLN 2:15)

- Trials must be confronted and alleviated, not passively endured (WSD 22:15)

The Kolbrin does not treat suffering as random misfortune or divine retaliation. It offers a structural explanation for why the righteous suffer alongside the wicked.

First, humanity is described as a single interconnected whole. The suffering of the innocent is often the consequence of collective failure, not personal guilt. Life does not operate on isolated moral units, but on shared conditions in which the actions of some inevitably affect others (SVB 5:34).

Second, suffering is presented as a necessary condition for awareness and value. Pleasure without pain would be meaningless; light without darkness would be unrecognizable. Without sorrow, joy would carry no weight and no depth (SVB 5:35).

Third, the Kolbrin states explicitly that it is not comfort, but suffering and sorrow, that have raised humanity to its present moral height. Through pain arise conscience, remorse, responsibility, and compassion — qualities unknown to lesser creatures who do not suffer in this way (SVB 5:36).

Finally, suffering is framed not as rejection, but as progression. Man is said to have already passed the simpler tests of existence and therefore must now walk the harder road. The trials of the righteous are not evidence of abandonment, but of readiness for greater responsibility and inheritance (SVB 5:37–38).

“It is because mankind is a single whole; if an arm is wounded the whole body suffers; men are not strictly divided into good and bad, guilty and innocent.” 10

“Just as the soulspirit experiences pleasure, so must it experience pain; were it otherwise, the pleasure would have no value.” 11

“It is suffering and sorrow, not pleasure and happiness, that have raised man to his present height.” 12

The righteous do not suffer because they are rejected, but because they are being formed.

8. Judgment Without Punishment: Law as Destiny

At the heart of the Kolbrin perspective lies a decisive clarification:

God neither rewards nor punishes arbitrarily.

He establishes the Law, by which each person determines his own destiny. 12

Judgment is not an external sentence imposed upon the soul. It is the revelation of what the soul has become.

9. Qur’anic Confirmation: Deeds Manifest, Not Assigned

This framework aligns seamlessly with the Qur’an:

- “Whoever does good, it is for himself; whoever does evil, it is against himself.” (41:46)

- “Whoever does an atom’s weight of good will see it, and whoever does an atom’s weight of evil will see it.” (99:7–8)

10. Why the Wicked Appear to Win

- the wicked often avoid early cost

- they live on deferred consequence

- their prosperity is unsettled accounting

- justice is delayed, not absent

11. Final Synthesis

Prosperity without transformation is postponement.

Suffering without despair is formation.