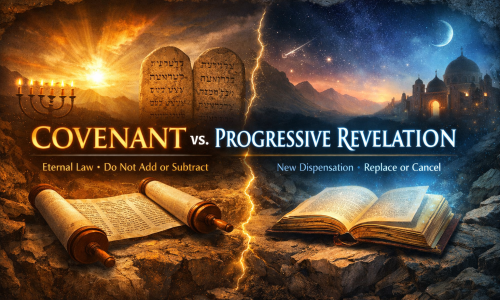

Covenant vs. Progressive Revelation: A Textual Q&A (Torah, Acts, Qur’an, Kolbrin)

Why this matters: People often mix two different categories—(1) laws inside an established covenant and (2) guidance for peoples outside that covenant. When those are confused, “progressive revelation” is used to justify replacing prior commandments. This post separates the frameworks using text-based criteria.

TL;DR

- Kashrut is covenantal (Israel), not universally imposed on all nations (Deut 14:21).

- The Torah’s prophetic test is not “public witnesses,” but covenantal fidelity (Deut 13; Deut 18).

- Regulations for non-covenantal peoples ≠ abolishing the covenant. Replacing/suspending an established covenant = the real issue.

- “New dispensation / progressive revelation” is a theological model; the Torah prohibits adding/subtracting from the covenantal Law (Deut 4:2; 13:1).

- The Kolbrin echoes the same criterion: conflicting/replacing prior established teachings = false prophet (SVB 7:11).

Part 1 — Dietary Laws and the Category Error

Question

“If we are honest and consistent, Muslims say that Muhammad permitted eating camel, rabbit, and similar animals, which Moses absolutely forbade. Does that make Muhammad a false prophet according to the Torah?”

Answer

This question is based on a false comparison and must be clarified textually.

1) The Torah never imposed dietary laws on non-Jews

Dietary laws (kashrut) are a sign of the Covenant with Israel, not a universal law for all humanity. The Torah explicitly distinguishes Israelites from the foreigner:

“You may give it to the foreigner who lives among you…” (Deuteronomy 14:21)[1]

So what is forbidden to an Israelite is not automatically forbidden to a non-Israelite. Therefore, judging a prophet as “false” for permitting what was restricted within Israel’s covenant is a category error.

2) The Qur’an does not abolish Israel’s covenant

The Qur’an repeatedly calls the People of Israel to return to and uphold their covenant and the Torah (e.g., Qur’an 2:40; 5:12–13; 5:44).[2] That is not the same thing as claiming, “what God commanded no longer applies.”

3) James formally exempts Gentiles from Mosaic law (Acts 15 & 21)

In Acts, James states Gentiles are not required to keep the Mosaic Law, but only basic prohibitions (Acts 15:19–20; 21:25).[3]

Conclusion: Dietary permissions for peoples outside the covenant are not the same as abolishing the covenant.

Part 2 — “Witnesses at Sinai” Is Not the Torah’s Criterion

Question

“Which legislative structure, and which Torah criterion for a true prophet? One Jewish objection is that Moses received revelation before hundreds of witnesses, while no one saw what happened in a cave. Is that the criterion?”

Answer

The “public witnesses” argument is a later polemical point, not a Torah-based test. The Torah does not say that a prophet must receive revelation in front of crowds to be true; many prophets receive revelation without witnesses.

The Torah’s explicit tests are here:

- Deuteronomy 13:1–5 — even signs/wonders do not validate a prophet who undermines covenantal fidelity.[4]

- Deuteronomy 18:18–22 — the Torah’s stated criteria for a true vs. false prophet.[5]

So what does “legislative structure” mean? It means the real issue is not where revelation happened (cave or public), but what it does to the already-established covenant. If a message nullifies what God declared binding, it fails the Torah’s test—regardless of spectacle, witnesses, or claims.

Conclusion: The relevant question is: Does the message confirm or undermine the established covenant?

Part 3 — “Every Messenger for His Own People” Is Not a Torah Model

Question

“So every messenger can bring and abolish laws for his people? Then the Bab did it for his people, Guru Nanak for his, Subh-i-Azal for his, Baháʼuʼlláh for his—everyone for their own. Then no one violated anything.”

Answer

This conclusion collapses two categories that the Torah keeps distinct:

1) The Torah does not teach parallel dispensational law systems

The Torah recognizes (a) the covenant with Israel and (b) the nations outside that covenant. It does not present a model where each nation receives a new law that can replace prior covenantal law.

2) Regulations for non-covenantal peoples ≠ abolishing the covenant

If someone brings guidance for a people who were never inside the Mosaic covenant, that is not the same as abolishing Moses. Deut 14:21 already implies this distinction, and Acts 15 & 21 formalize it for Gentiles.[1][3]

3) The violation occurs only here

The Torah’s problem is specifically this: when someone abolishes/suspends what God already declared binding within an established covenant (Deut 13; Deut 18).[4][5]

Conclusion: “No one violated anything” only works if you erase the covenant/non-covenant boundary—which the Torah itself does not erase.

Part 4 — “New Dispensation / Progressive Revelation” vs. Covenant Permanence

Question

“He doesn’t say ‘God’s commands no longer apply’—it’s a new dispensation. Progressive revelation. The Bayan was intentionally unfinished until the one whom God will manifest appears…”

Answer

Changing the label does not change the effect. Whether someone says “this no longer applies” or “it applied then, now we move forward,” the result is the same if a binding covenantal command is annulled.

The Torah’s position is explicit

- Do not add or subtract from the commandments (Deut 4:2; 13:1).[6]

- The covenant is described as enduring (olam) (e.g., Gen 17:7; Ex 31:16).[7]

So a “progressive dispensation” that suspends an existing covenant is not a Torah mechanism—it is a different theological framework imported from outside the Torah.

Kolbrin parallel criterion

“...for if a prophet sets up a body of laws conflicting with established teachings, or laws claiming to replace them entirely, he is a false prophet.” (Kolbrin, SVB 7:11)[8]

Honest conclusion: One may personally adopt progressive revelation, but then one must acknowledge that this departs from the Torah’s stated covenantal criteria—it does not fulfill them.

Footnotes

- Deuteronomy 14:21 — distinction between Israelite dietary restrictions and the foreigner.

- Qur’an 2:40; 5:12–13; 5:44 — calls to uphold the covenant/Torah.

- Acts 15:19–20; Acts 21:25 — Gentiles not bound to Mosaic Law; basic prohibitions only.

- Deuteronomy 13:1–5 — prophetic test prioritizes covenantal loyalty over signs/wonders.

- Deuteronomy 18:18–22 — Torah’s criteria for a true vs. false prophet.

- Deuteronomy 4:2; 13:1 — prohibition of adding/subtracting from the commandments.

- Genesis 17:7; Exodus 31:16 — covenant described as enduring (olam).

- Kolbrin, Book of the Silver Bough (SVB) 7:11 — false prophet: laws conflicting with or replacing established teachings.